Although sleep centers have significantly improved access to sleep medicine, we often lack psychologists with specialty expertise in sleep medicine on our teams. Consequentially, most sleep centers are unable to offer the first-line, recommended behavioral therapies to patients with complex insomnia, circadian rhythm sleep/wake disorders, and difficulties with PAP therapy adherence.

The evidence for the effectiveness of behavioral interventions for sleep disorders is compelling. Did you know that cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is cost-effective compared with pharmacotherapy or no treatment?1 Studies also show that patients who undergo CBT-I versus pharmacological therapy still show improvements after ten years!2

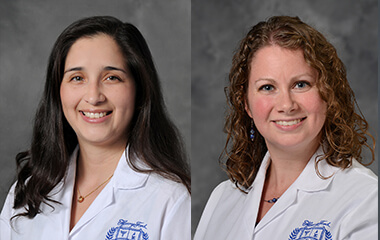

To gain a better understanding of how an exemplary multidisciplinary sleep team works, we interviewed Drs. Luisa Bazan, head of the division of sleep medicine and program director of the sleep medicine fellowship at Henry Ford Health in Detroit, Michigan, and Maren Hyde-Nolan, clinical sleep psychologist at Henry Ford Health. These providers not only integrated behavioral sleep medicine into their medical sleep center, but they had so much success that they are now planning to expand its services. We spoke with them to learn more about the challenges and successes of adding behavioral sleep services to their busy practice.

Please describe the sleep center.

Dr. Bazan: Our sleep center has seven clinics in the Detroit area and a diverse senior staff that sees approximately 19,000 patients, 3,000 in-lab and 4,500 home sleep apnea tests a year.

What considerations factored into the initial decision to create a position for a sleep psychologist in the medical sleep center?

Dr. Bazan: We wanted to invest in a specialized sleep medicine clinic to provide better quality care for our patients, especially those with insomnia and circadian rhythm disorders. Psychologists have longer visits than physicians and can provide care for clinical complexities that require more time. It also allows physicians to see more patients requiring sleep studies, which also generates more revenue for the clinic. Having a psychologist on our team has also enhanced the culture of care on our team.

What challenges have you encountered, and how have you managed those challenges? What have been some positive changes?

Dr. Bazan: Our initial challenges included working with insurance and raising awareness about our services. We worked hard to spread the word, and it took two to three years to build the awareness; but now, our waitlist is so long that we’ve had to slow down new-patient intakes. To meet this demand, we will be expanding our behavioral sleep medicine clinic!

Please describe yourself and your practice. What percent of your practice are sleep patients? How do you bill (e.g., mental health vs medical)?

Dr. Hyde-Nolan: I am the clinical sleep psychologist embedded within the sleep center and only treat sleep patients and bill through behavioral health (i.e., psychotherapy codes). Ninety percent of my case load is insomnia patients, and the rest include sleep apnea complications, circadian rhythm disorders, and hypersomnia.

How have you grown your caseload? How long did it take?

Dr. Hyde-Nolan: We began with internal referrals, but that was not enough to fill my caseload. Over a period of about two or three years, I sent letters to other sleep centers in the area and visited primary care clinics to provide presentations about our services. The referrals started pouring in at the beginning of the pandemic, and it has only escalated ever since. It helped that I was already set up to do virtual visits since we have seven clinics and just one psychologist. My caseload is now 100% virtual.

What are some advantages of being a sleep psychologist in a large medical sleep center? What are some challenges?

Dr. Hyde-Nolan: I have support from a wonderful multidisciplinary team. I love working alongside my physician and nurse practitioner colleagues; we often bounce ideas around especially because we have such diverse expertise. That said, it is also clear that I provide a service that no one else does, and there are a lot of sleep patients out there who need to see a psychologist. I also teach behavioral sleep medicine to the sleep medicine fellows.

In terms of challenges, I have found that because psychological services are typically underrepresented in medical sleep centers, it is important that there is education and advocacy for the role of psychologists in sleep medicine, especially since my role differs in significant ways. Growing the clinic was also a challenge!

What advice do you have for other sleep centers that might be considering adding or expanding behavioral sleep medicine services?

Dr. Bazan: Although it takes resources and commitment to get the service set up, it really is a win-win. It is the right thing to do for the patients, and it can significantly enrich the entire sleep center.

Dr. Hyde-Nolan: It is important to make connections with others in the field who are doing what you want to do. I was excited to learn about the AASM Psychologist Assembly for this reason! I think there are a lot of opportunities for advocacy for sleep psychologists.

If you are a sleep psychologist and interested in working within a sleep center, go to the AASM Career Center (https://career.aasm.org/). There you can upload your CV and enroll in an email job update based on your search criteria.

Deirdre Conroy, PhD, DABSM, DBSM, FAASM, and Philip Cheng, PhD, are chair and vice-chair of the AASM Psychologist Assembly. This article appeared in volume eight, issue two of Montage magazine.

References

- Natsky AN, Vakulin A, Chai-Coetzer CL, et al. Economic evaluation of cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) for improving health outcomes in adult populations: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;54:101351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101351

- Jernelöv S, Blom K, Hentati Isacsson N, et al. Very long-term outcome of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: one- and ten-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther. 2022;51(1):72-88. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2021.2009019