An estimated 30 million adults in the U.S. have obstructive sleep apnea. The leading treatment, CPAP therapy, offers patients the chance of a restful night’s sleep without waking up from obstructed breathing and a lack of oxygen. By blowing a stream of air into the throat, the CPAP machine allows patients to breathe easier.

However, patients’ long-term CPAP adherence varies widely, hovering near a worryingly low 50% in some populations, with many citing device comfort as a challenging roadblock.

Faced with the desire to improve patient comfort and adherence, William Noah, MD, began to question the way CPAP machines work.

Dr. Noah is the founder and medical director of Sleep Centers of Middle Tennessee with clinic locations in multiple cities including Murfreesboro, Franklin/Nashville, Clarksville, and Chattanooga. He is a founding member of the Middle Tennessee State University Sleep Research Consortium and the CEO of SleepRes, LLC.

A physician by trade, Dr. Noah sacrificed his spare time to research PAP devices and scour them for areas of improvement. He dove into the physiology and physics of the PAP circuit to better understand how the device works. He began to question what he knew about inspiratory and expiratory pressure.

Armed with a hypothesis, he built a sleep research lab in his basement during the pandemic and conducted his own research and interviews.

Despite the sleep field’s 30-year-old focus on the importance of greater inspiratory pressure, a discovery in Dr. Noah’s lab led him to suspect that PAP devices are not optimally engineered.

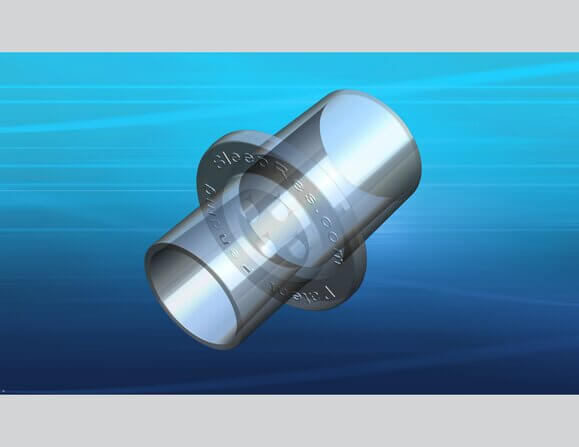

In 2021, he developed V̇-Com, a comfort device intended to improve PAP adherence based on the theory that lowering inspiratory pressure could increase comfort while continuing to treat obstructive sleep apnea – a theory that several pioneering CPAP engineers now support.

“Since I was fortunate enough to convince the FDA in late ’84 to approve CPAP and then later approve BiPAP, the mode has been driven by engineers,” said Eugene Scarberry, a retired senior engineer at Philips Respironics. Scarberry was a part of the first commercial patent for CPAP and integral to the team that invented BiPAP.

“What makes the V̇-Com unique is that it came from a physician who is also a user and saw an unmet need that manufacturing had not solved,” Scarberry added.

After printing a 3-D prototype at a local university, completing months of testing, and convincing even himself of the significance of the data, Dr. Noah manufactured the device and launched it last June at the SLEEP 2022 annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies (APSS) in Charlotte, North Carolina.

While there’s still more research to be done, the sleep community finds the early evidence compelling. Hundreds of professionals experienced Dr. Noah’s invention first-hand at the SleepRes booth at SLEEP 2022. SleepRes likens the device to “training wheels for CPAP.”

Montage talked with Dr. Noah about his game-changing idea and his invention of the V̇-Com, a CPAP accessory that could improve both comfort and adherence for patients.

Montage: What prompted your interest in creating the V̇-Com? Can you describe what problem it solves?

William Noah: My interest has always been increasing PAP adherence. We pioneered using modems with every CPAP patient back in 2006 and collected long-term adherence data on 6,000 consecutive patients from 2012 to 2017 that just finally came out in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine in January 2021. Everything I had done thus far to increase adherence was mainly based on behavioral change.

So, in spring of 2021, I started researching PAP devices and masks to see if I could find some improvement. I interviewed tons of people in the field (physicians, RPSGTs, RTs, and manufacturing engineers) and built a lab to begin testing equipment. I had almost every device and mask made in the world in my lab to play with. I had to relearn a bunch of physics and calculus.

The first thing I discovered is kind of embarrassing. I didn’t understand PAP devices and masks nearly as well as I thought I did. I found out from interviews that my peers were similar. I found a great disconnect in the field. Physicians know the physiology, but not the engineering, and the engineers are the reverse.

Early PAP devices had lower inspiratory pressure (IPAP) than expiratory (EPAP); then in 1990 bilevel PAP (BPAP) was introduced with IPAP > EPAP. Somehow the field grasped onto the concept that IPAP was needed to treat hypopneas and that lowering EPAP would increase adherence. We have been taught EPAP was the problem for 30 years, and most patients today are treated with IPAP > EPAP (mainly with expiratory pressure reduction and mask compensation algorithms, not BPAP). Yet IPAP > EPAP has not improved adherence, and EPAP is the more effective therapy for hypopneas, not IPAP.

Through testing I realized that IPAP was more offensive to new patients. My hypothesis was that if I could decrease inspiratory pressure (and flow), I could possibly make PAP more comfortable for new patients, and that the 30-year focus on IPAP was misguided. I also hypothesized that reducing IPAP would decrease adverse effects of PAP including the risk of rebreathing, treatment-emergent central sleep apnea, and aerophagia.

Montage: Can you describe the process of inventing the V̇-Com, from conception to sale?

WN: Since no current bilevel device can lower IPAP less than EPAP, I had to figure out another way to do it. My research involved adding non-compensated resistance to the circuit to take advantage of the parabolic nature of the pressure drop with turbulent flow. It worked, so I 3-D printed initial prototypes of the future V̇-Com in July of 2021 and tested them on myself and colleagues. The data were excellent, but I just couldn’t believe we were wrong all those years. It took me six months of further testing to convince myself. Then in January 2022, I decided to manufacture it, complete FDA/ International Organization for Standardization (ISO) testing requirements, and release it at SLEEP 2022 in June. Then I could put it on patients and collect even better data.

Yes, we released the V̇-Com to sell, but for me it was more to prove my hypothesis and improve the comfort for my patients.

Montage: How did you find the time to develop and launch this device, in addition to your work as a physician?

WN: That is the tough thing. I don’t get paid or have protected time to do research. It is basically volunteer work. And it is a lot of work. Adding work adds stress. You give up weekends. You give up travel and hobbies. It is not good for your health. (Take time to exercise, get check-ups, and eat right). Fortunately, my wife is very understanding and supportive. My golf buddies are not quite as understanding and harass me regularly to play. They call me the lab rat now.

Montage: What type of reception did the V̇-Com get when it was introduced at SLEEP 2022?

WN: It was wonderful. The interest was overwhelming. The booth was so crowded, people couldn’t get down the aisle in front. We had over 300 sleep physicians (not counting PhDs, NPs, PAs, RTs, RPSGTs, industry executives, etc.) not just visit the booth but actually wear CPAP in the booth with and without the V̇-Com. (Each obviously had a new mask to use donated by the manufacturers). All but five could feel a significant difference in comfort (and three of the five were long-term users). In a post APSS survey, 96% of responders who tried the V̇-Com believed every patient should get one. Manufacturers met with me at APSS as well to discuss providing V̇-Com with their devices.

Montage: Do you have plans to expand into more products? What’s on the horizon?

WN: In my current research, I am writing new algorithms to make PAP devices more comfortable and safer. Yes, there is a safety issue my research has found that we are about to release. My research has also developed new mask technology. I made the first prototypes last year. We don’t want to manufacture, but we easily could. Masks are easy, but we would rather put the technology from my research into others’ products.

Montage: What advice do you offer to someone determined to bring about change or innovation in the sleep field?

WN: Be your own biggest critic. When you think you have tested it enough, test it again. Read all the original studies because someone probably thought like you long ago, but never did anything about it. After that, find the smartest people with expertise in your area who would normally disagree with you and convince them. But be prepared; no matter how many people brag about your innovation, it takes time for people to change practice. Fortunately, for us that time has been short.

By Kate Robards, AASM Digital Communications Coordinator. This article appeared in volume eight, issue one of Montage magazine